When the Devil offers you a deal, it takes balls to negotiate the terms and conditions, but that’s exactly what Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski did when they made their mark on the movie industry. Their rebellious nature and determination resulted in some of the most unique films of the 1990s, including the essential biopic of HUSTLER founder Larry Flynt, in The People vs. Larry Flynt (released in 1996).

Their first script Homewreckers got stuck in development hell and never made it to the screen, but their second (Problem Child) was green-lit and became a huge financial success for the studio (Imagine/Universal). The end result, however, was very different from the original tone and intention that the writers set out to create. What was initially meant to be a very black comedy about how awful children can be was reduced to a puerile mixture of infantile slapstick and toilet humor. This left the writers in a conundrum. They were considered hot in Hollywood, and the studios all wanted to work with them, but now they had an indelible reputation as the guys who made kiddie comedies, and so their more outlandish pitches weren’t even given the time of day. They wanted to tread new ground. A change was in the cards.

Alexander and Karaszewski made a conscious decision to rebrand themselves and forge a career in the manner of which they had originally desired. They returned to their roots, into the world of American independent cinema. Casting their minds back to their student days at USC in the early ’80s, they focused on a lingering obsession for a project; the life and work of Edward D. Wood Jr. Assembling a treatment, they presented it to several directors (including Michael Lehmann and John Waters), but it was through Heathers alumni Denise Di Novi that the project was passed on to Tim Burton. The writers wanted him to lend his name as an executive producer (or “Presents” credit) so that they could generate more funds for the film. Burton loved it, expressed his desire to direct, and the rest is history. Suddenly Alexander and Karaszewski’s little movie about an oddball exploitation filmmaker had transformed into an Oscar-winning behemoth that used mainstream cinema to change the way we looked at the outsider.

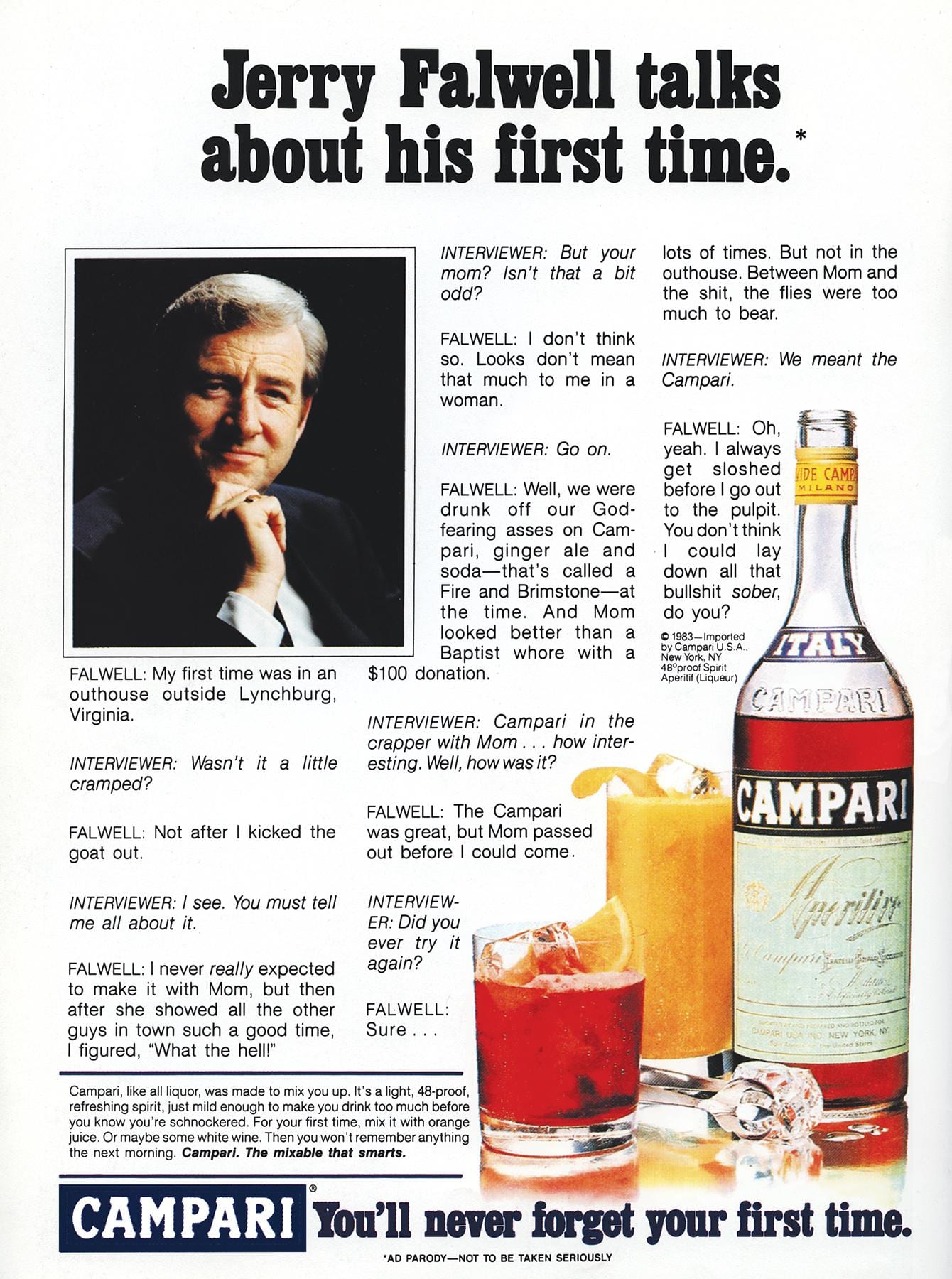

Realizing there was a short window to capitalize on this opportunity, the pair immediately began piecing together information on one of their other obsessions: Larry Flynt. During their college years, the stories of Flynt’s escapades had dominated the Los Angeles Times, and they followed every movement in detail. Here was a pornographer who ran for president, a man who was shot for what he believed in, yet still would not be silenced. He was, in many ways, an American icon, albeit an unconventional one. Flynt was someone who continually used his money to “push buttons” as Karaszewski puts it.

“We consciously cooked up Larry Flynt, almost like a sequel to Ed Wood,” notes Alexander. “We used to joke that we only had two ideas for movies, two dream projects which both got made.”