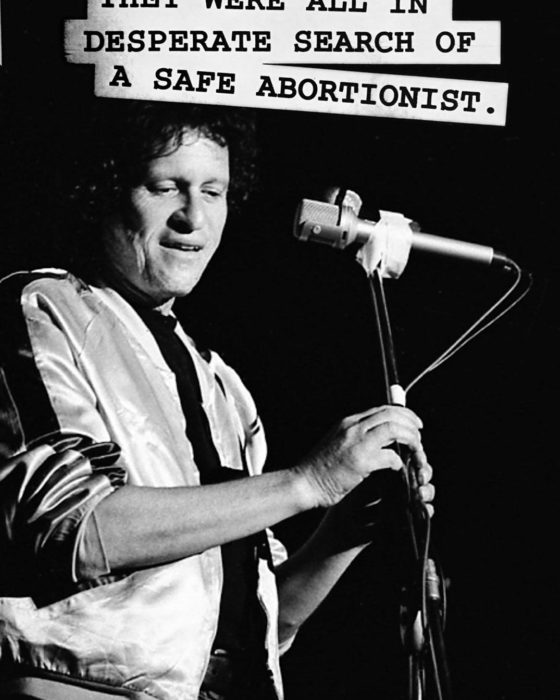

Three years before his death in 2019, Paul Krassner, longtime satirist and activist, recounted for HUSTLER the history of abortion in his lifetime—from illegal to legal, to the deterioration of a woman’s reproductive rights once again. He detailed the past, when he ran an underground abortion referral service, and warned of a dangerous future…

When abortions were illegal in America, women had no choice but to seek out back-alley butchers for what should have been a medical procedure in a sterile environment. If there was a botched surgery and the victim went to a hospital, the police were called, and they wouldn’t allow the doctor to provide a painkiller until the patient gave them the information they sought.

In 1962 an article in Look magazine stated, “There is no such thing as a ‘good’ abortionist. All of them are in business strictly for money.” But in an issue of my own magazine, The Realist, that same year, I published an anonymous interview with the late Dr. Robert Spencer, a truly humane abortionist, promising that I would go to prison sooner than reveal his identity.

He had served as an Army doctor in World War I, then became a pathologist at a hospital in Ashland, Pennsylvania. At a time when 5,000 women were killed each year by criminal abortionists who charged as much as $1,500, his reputation had spread by word of mouth, and he was known as The Saint. Patients came to his clinic in Ashland from around the country.

I took the five-hour bus trip from New York to Ashland with my gigantic Webcor tape recorder. Dr. Spencer was the cheerful personification of an old-fashioned physician. He wore a red beret and used folksy expressions like “by golly.” He had been performing abortions for 40 years. He started out charging $5 and never asked for more than $100. He rarely used the word pregnant. Rather, he would say, “She was that way, and she came to me for help.”

Ashland was a small town, and Dr. Spencer’s work was not merely tolerated; the community depended on it—the hotel, the restaurant, the dress shop—all thrived on the extra business that came from his out-of-town patients. He built facilities at his clinic for African-American patients who weren’t allowed to obtain overnight lodgings elsewhere. The walls of his office were decorated with those little wooden signs that tourists like to buy. A sign on the ceiling over his operating table said, “Keep Calm.”

Here’s an excerpt from The Realist interview: