When the strippers of Star Garden in North Hollywood, California, went on strike in February 2022, they were not expecting to still be on the picket line seven months later. “None of us knew what we were getting into,” Charlie, one of the striking dancers, recalls. “We kind of thought it would be a two-week thing, and then we’d just go back to work.” On a chilly October Friday night, the picket line assembled, as it had once per week for the previous 29 weeks. Strippers, other sex workers, Star Garden customers, union workers from various industries and community members held signs emblazoned with slogans such as “Power to the Strippers” and passed out flyers about the strike to anyone heading for the club entrance. Despite it being a weekend, only a handful of potential patrons came by, and over half were persuaded to boycott. In fact, some of Star Garden’s regulars had become regulars at the picket line instead. The strike, it seemed, was more of an attraction than the club.

This was the first picket line after a victory for the strippers: They had been granted an election by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), a big step forward in the process of forming a union. If more than half the votes cast by Star Garden workers favored unionization, the union would be certified as a representative for collective bargaining, and management would be required by law to participate in contract negotiation. This would make Star Garden the only union strip club currently in the States. Key demands: an end to wage theft and racist, discriminatory hiring practices; adequate safety measures in place and enforced; and a just-cause policy for termination. “I’m really excited to get a union contract because we’ll finally be able to negotiate over the terms of our work,” Velveeta tells HUSTLER.

The strike started in the wake of two Star Garden dancers being fired after they brought up safety concerns to management. They requested the club not allow customers to film stage shows or hang out at the bar after hours. Following the firings, management implemented a policy forbidding strippers from reporting customers directly to security. Instead, they were instructed to talk to a manager first. This presented an obvious conflict of interest, but in addition, there was not a manager on duty at all times, leaving dancers unable to deal with immediate safety problems per the rules of the club. “We all just thought that was ludicrous, so we formed a petition,” Charm recounts. “We asked for that rule to be rescinded. We asked for our coworkers who were fired to be reinstated. We asked for copies of our contract and copies of the employee policy handbook.” The night after they delivered the petition, they were locked out of the club. It was at that point that the workers started talking about unionization.

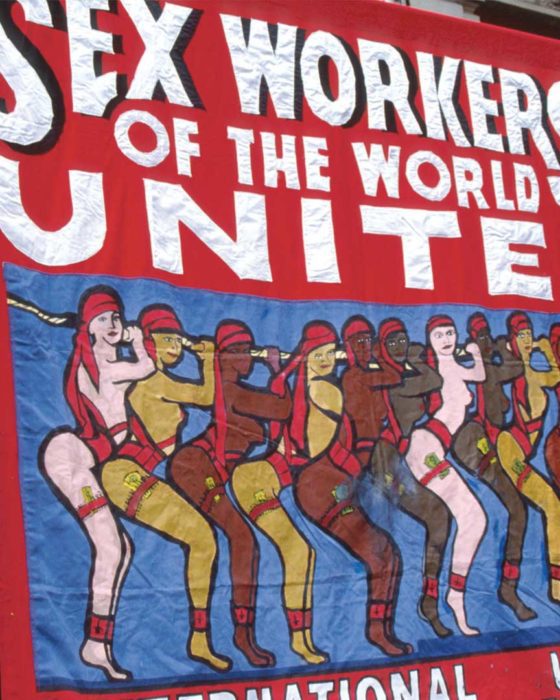

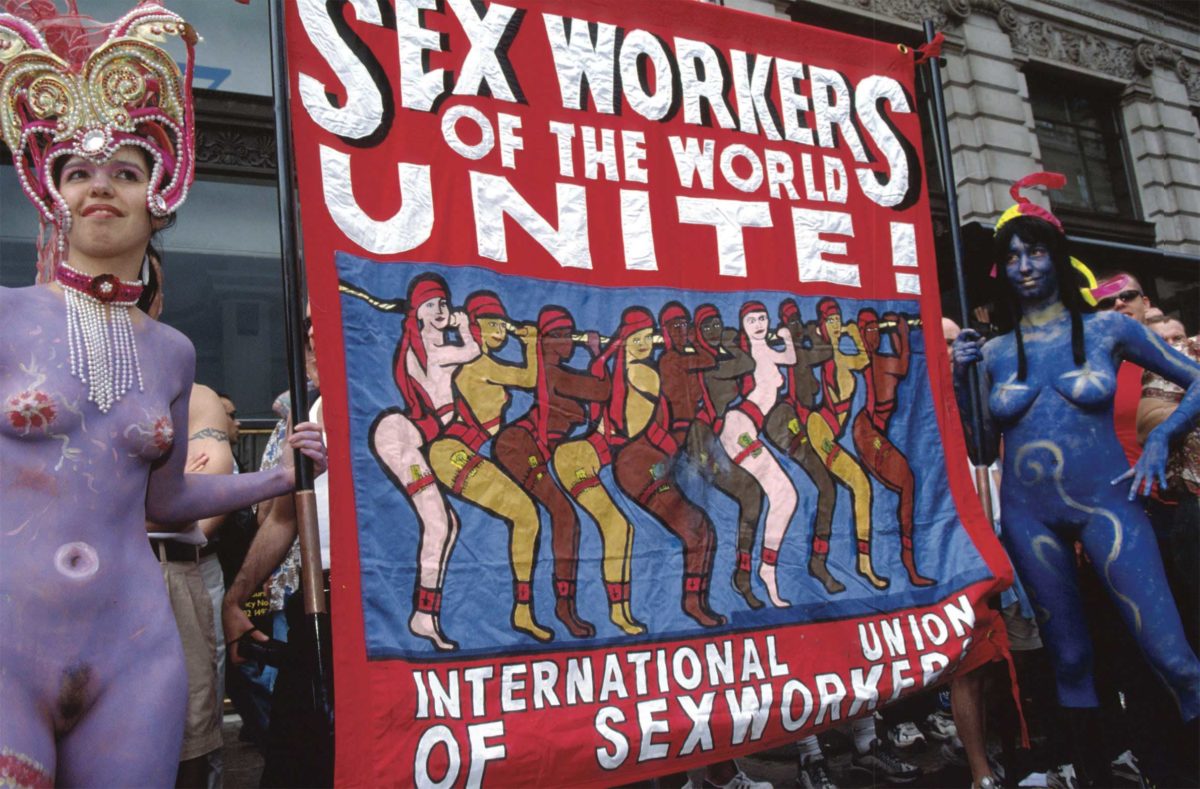

With themes, games and costumes, the striking strippers captured the attention of the media and internet, particularly one night in April, after they filed an OSHA complaint against Star Garden and dressed up as the club’s workplace safety violations. What happened next surprised them: They were applauded and embraced. Reagan says, “We were so scared, but everyone has been so nice!” The strippers were not demeaned or derided, for the most part. They were taken seriously, not only in the press, but by other unions. Members of unions across many industries picketed with them in solidarity, notably Chris Smalls, president and founder of the Amazon Labor Union. This turn of events was a shift; for sex workers, misrepresentation in the media and disrespect from other workers is the norm. In the past, the concept of a strip club union was mocked and treated as a novelty by much of the mainstream media, specifically in the coverage of the Lusty Lady’s now-famed strike and unionization in 1997.

San Francisco’s Lusty Lady peep show was the first strip club to unionize in the U.S. It was later purchased by the strippers to run as a worker cooperative, in which all employees were entitled to receive a portion of the club’s profits. AVN award-winning porn performer Daisy Ducati was a dancer at the Lusty Lady after it was unionized: “The union was very strict about how we were allowed to be treated and how people were allowed to be fired…[management] had a very specific set of standards for hiring and firing. Pretty much, if the job was open and the person was qualified, then they would get hired…you couldn’t get fired just because a manager didn’t like you, or just because you’re brown, which was a huge thing before the union.” As a co-op, the Lusty Lady made administrative decisions democratically at company meetings, where attendance had to reach quorum to take a legitimate vote. “Sometimes that was a little difficult,” Daisy says. “But we were involved in pretty much all of the decision-making.”

Daisy was working at the Lusty Lady when it closed in 2013, after a consultant was brought in to help address financial troubles. This consultant then signed an agreement with the landlord to close the club, despite lacking the authority to sign such an agreement. Unfortunately, it was too late to save the Lusty Lady. “Our lawyer was thoroughly convinced that the agreement was binding and there was no way out of it,” Daisy says. According to her, although the club was having money issues, they were nowhere near the point of needing to immediately shut down. To this day, the building that once housed the Lusty Lady remains empty.